TRACKS

| 1 | Drought |

| 2 | Deja’Vu |

| 3 | Highway |

| 4 | Ephemeral Lakes |

| 5 | Log Dance |

| 6 | Choppers |

| 7 | Emu |

| 8 | Bullant |

| 9 | Rainforest |

| 10 | Landmark |

| 11 | Troppo Wet |

| 12 | Bedrock |

| 13 | Danger |

THE BAND/ARTISTS

| Charlie McMahon | – | didjeridoo, vocals, didjeribone |

| Peter Carolan | – | synthesiser |

| Eddie Duquemin | – | drums, percussion |

THE RECORDING

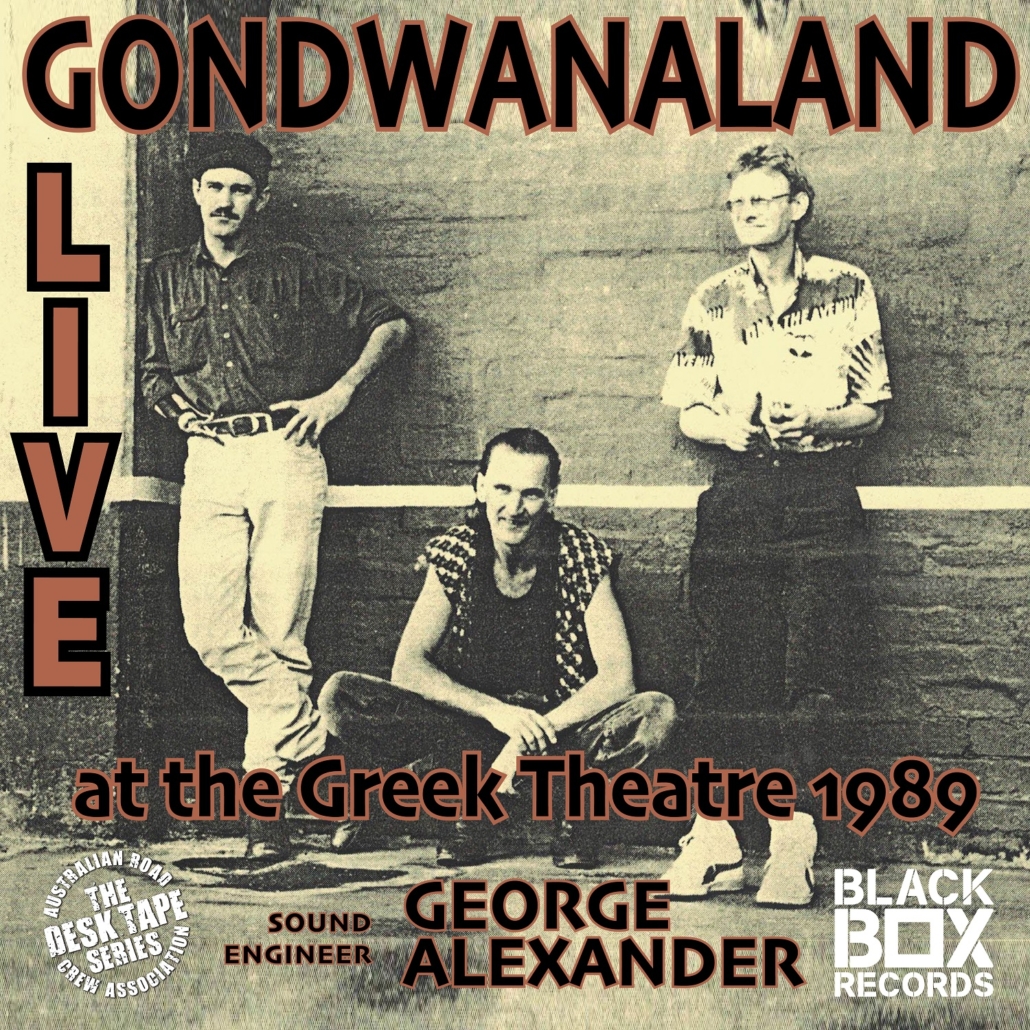

Gondwanaland

Live at the Greek Theatre 1989

All the ARCA Desk Tape Series recordings are available through Black Box Records – australianroadcrew.com.au

Mastering:

Phil Dracoulis

THE CREW

| George Alexander | – | Front Of House |

| Phil Free | – | Monitors |

| Steve Pauner | – | Lights |

| Terry Fisk | – | Lights |

| Lash | – | Stage |

WHO WE ARE

The Australian Road Crew Association Limited (ACN 684 129 468) (ARCA) is a non-profit company limited-by-guarantee dedicated to helping Road Crew Past and Present.

Road Crew are the collective backbone of the Australian music industry. Road Crew have technical ability that are unique and wide ranging. Without dedicated Road Crew there would be no Live Production.