CREW

Archie Roach

Ruby Hunter

BAND

Mark Woods (sound / Key Largo)

Natalie McNaut (lights)

Andy Rayson (sound / Darwin Casino)

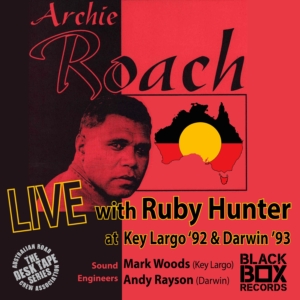

Archie Roach is the 26th act to throw his support behind Support Act’s Roadies Fund through the Australian Road Crew Association (ARCA)’s Desk Tape Series.

The Series was created by ARCA to raise funds to provide financial, health, counselling and well-being services for roadies and crew in crisis. The recordings are made off the sound desk by a crew member – in this case Mark Woods for the US show in Portland, Oregon at the Key Largo in ‘92, and Andy Rayson for the Darwin Casino in ’93 – and released on ARCA’s Black Box Records through MGM Distribution and on all major streaming services.

Thanx to Mark Woods for the cover photo, Tony Mott and NFSA for other photos, Nprint for the artwork, Phil Dracoulis for the mastering, and especially Archie Roach for his support of roadies and crew in crisis.

TRACKS

- Charcoal Lane (Key Largo)

- Tell Me Why (Key Largo)

- Down City Streets (Key Largo)

- Aunty Sissy (Key Largo)

- Change Gonna Come (Key Largo)

- Weeping In The Forest (Key Largo)

- Took The Children Away (Key Largo)

- No No No (Key Largo)

- Keep Me Warm (Key Largo)

- Sister Brother (Key Largo)

- From Paradise (Key Largo)

- Life Is Worth Living (Key Largo)

- Walking Into Doors (Darwin Casino)

- Sister Brother (Darwin Casino)

- So Young (Darwin Casino)

- Beautiful Child (Darwin Casino)

- From Paradise (Darwin Casino)

THE BAND

Archie Roach

Ruby Hunter

THE CREW

Mark Woods (sound / Key Largo)

Natalie McNaut (lights)

Andy Rayson (sound / Darwin Casino)

Archie Roach LIVE in Key Largo ’92 and Darwin ’93 shows the healing continues each time he plays a concert – both for himself and the audience.

“It’s a two-way thing,” the Gunditjmara / Bundjalung man said. “The audience gives me so much back – it’s hard to explain.

“But that’s actually what I do this for … to get that interaction with the audience.”

Paul Kelly, who co-produced Archie’s first album Charcoal Lane, said, “Everything we do is political. No one bears that out better than Archie. All his songs are love songs – love songs to country and clan – and at the same time they cry out for a better world.”

He added: “He refuses to despair. Although many of the stolen children never came back, and although many of the children of the stolen have never known the way, Archie still keeps singing them home.”

Kelly helped kickstart Archie Roach’s career in 1990 by putting him on as a support at a gig with The Messengers at Melbourne Concert Hall (now Hamer Hall).

Messengers guitarist Steve Connolly had seen him perform ‘Took The Children Away’ on ABC TV show Blackout and told Paul: “I’ve just seen the most amazing singer on TV. We should get him.”

Archie’s first song that night was ‘Beautiful Child’. Total silence from the sold-out crowd. Then came ‘Took The Children Away’. Again total silence. Just the sound of crickets outside.

Feeling he’d bombed, he began walking off the stage, promising himself, “I won’t do this again.”

Realising he’d finished, the 2,466 people in the audience began clapping.

“It sounded like rain, you know how rain starts with a pitter-patter, and it builds up, becomes a downpour?

“It was the most amazing experience I’d ever had. I felt this elation. I put my guitar up over my head, like, YEAH, and I walked offstage.”

Greeting him side-stage, Paul Kelly told him it was the most powerful thing he’d ever seen.

He and Connolly chased him up and offered to produce an album and get him a record deal.

Archie was reluctant. He just wanted to remain playing gigs to his people and having community radio stations play live versions of his music.

“I didn’t want to lose my anonymity,” he explained.

He ran it past his wife and muse, Ruby Hunter.

She looked down at her feet and then, hands on hips, looked straight at him.

“It’s not all about you, Archie Roach.”

Archie knew immediately what she meant. “Because when one Aborigine person shines, we all shine.”

Archie Roach LIVE in Key Largo ’92 and Darwin ’93 captures the early part of their careers.

The US and Canadian tour was the first time they had been on a plane, much less been out of Australia, so much of it was a culture shock.

The three-month trip consisted of a six-week headliner run of small folk clubs, and another six weeks opening for Joan Armatrading.

Canada and the US took to the Australians immediately because of the emotion and reality of the shows, said Mark Woods.

“The folk clubs were intimate and beautiful, they sat about 100 people.

“They loved the songs about the Stolen Generation, they hung on every word, they’d all be crying every night because it was very genuine and very raw.

“Archie wasn’t a natural showman but he was very fit and striking looking, and he did like the fame.

“He and I were similar, we were the same age to the month, and we had the same education.

“When he was aged 11 and living with the Coxs (his third foster family who were loving Christians and turned him onto music) he was studying Shakespeare.”

The shows with Joan Armatrading were larger, to crowds of between 3,000 and 5,000, which meant Archie and Ruby had to quickly learn to project on stage and be louder.

At the end of the tour, they got a letter from an American folk legend.

She explained her record company had sent her a copy of his album.

“They thought I’d like your music. I love it!

“Sorry I missed your appearance in the Bay Area. Next time I won’t.

“Give me a call if you just want to say hello. All the best to you.”

The letter was dated August 13, 1992. It was signed Joan Baez, who in the ‘60s was Queen of Folk to Bob Dylan’s King of Folk.

The Darwin Casino show, to a few hundred fans, showed Archie becoming more confident.

It was recorded by Andy Rayson, who was based in Darwin from the beginning of 1992 to the end of 1995, working with local and islander First Nation bands, touring southern acts along the Top End, serving as technical director of the Pacific School Games and the Barranga festival.

What he remembers about the show was how the audience lapped up Roach and Hunter, and the battle he had with the PA system!

“It was built by a local electrician and it was the first time it had been used.

“It was full range, no fancy effects or electronics, nothing to control feedback, no crossovers, I was concentrating on getting that big airy sound.

“By the end of the show I was covered in sweat. I winged it but I got a good sound!”

The standout on the ARCA live tape, of course, is ‘Took the Children Away’ which brought to attention the plight of the Stolen Generation.

Initially when he started writing songs, they were country music themes.

During a visit to Framlingham Aborigine Mission on Gunditjmara country in south-western Victoria – where he grew up as a toddler until he and his siblings were seized by authorities – an elder, Uncle Banjo Clarke, told him he should be writing songs about being stolen.

Archie said he could hardly remember as he was just two or three.

“But I do,” Uncle Banjo responded. He told of the day the authorities came.

As the song recounted, “One dark day on Framingham / Came and didn’t give a damn / My mother cried, ‘go get their dad’ / He came running, fighting mad / Mother’s tears were falling down / Dad shaped up and stood his ground / He said, ‘You touch my kids and you fight me’ / And they took us from our family.”

Another Uncle Banjo recollection, which yielded ‘Weeping In The Forest’ was about how the forest became silent without children playing.

‘From Paradise’ relates: “And they took her away from Paradise/ Where everything was beautiful/ And very nice/ They took her away/Her mother’s tongue/ Slapped her around a little bit/ To teach her another one.”

‘Down City Streets’, written by Hunter, and ‘Charcoal Lane’ recall their days on the street – of the warmth and camaraderie they found with other indigenous people, like’ Aunty Sissy’.

Charcoal Lane, after which he named his debut album (on Mushroom) is an alley off Gertrude Street in Fitzroy where the homeless hung out.

From 2009 to 2021 it served as a fine dining restaurant which trained 300 First Nations hospitality staff, and currently occupied by the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service.

‘Change Gonna Come’ is about breaking the cycle of domestic violence, and ‘Life Is Worth Living’ is a warning to one of his sons who’s flirting with the wrong end of the law.

In ‘Old So And So’ (not included on this tape) he recalled the day he met Ruby.

At 17, after a stint picking grapes in Mildura in country Victoria, Archie stood on the side of the Sturt Highway, smoked three cigarettes and flipped a 20 cent coin to decide where to go next.

Heads was Adelaide where he’d never been, tails was back to Melbourne to his siblings who had rediscovered a few years before.

A few days later he was in Adelaide, staying at a run-down Salvation Army accommodation called People’s Palace on Pirie Street.

While waiting at the lift, out stepped a 16 year old girl in a blue dress, white cardigan, black shoes and the biggest brown eyes he’d seen.

He asked her where the local indigenous people socialised. She said, “Follow me”. He’d quip, “And I did… for 38 years.” He added “She never stopped talking…and had a glint in her eye.”

The Ngarrindjeri 16-year-old was stolen at eight from her grandparents’ home in South Australia’s Coorong region. The authorities had told they were taking her to the circus.

Hunter died from heart failure in 2010, aged 54. The world lost a beautiful soul.

In Philippa Bateman’s documentary Wash My Soul In The River’s Flow about their love story, Ruby quipped, “Archie is my silent hero and I’m his rowdy troublemaker.”

Onstage Ruby wore a headdress made from pelican feathers from Coorong rock cockatoo feathers, raffia, sequins and mirrors.

The pelican “is really Ruby’s spirit”, Roach noted. “In the dreamtime she was a pelican, before she came to Earth and was born as a baby girl.

“When she passed away, of course, she became a pelican again.”